A strong thread of criminality runs throughout Great Expectations, much as it did in everyday Victorian London. Charles Dickens himself was of course no stranger to the “wrong side of the law”. As a young man, his father served time as an insolvent debtor in Marshalsea Prison, and for a while Dickens worked as a court reporter. He also lived in a time of great social change, brought about by the increase in population, the impact of technological advances, the rise of industry; but also a rise in crime.

The rising crime figures were a consequence of the abject poverty and the government decided to increase the severity of the law – and particularly the punishment for petty crimes such as theft.

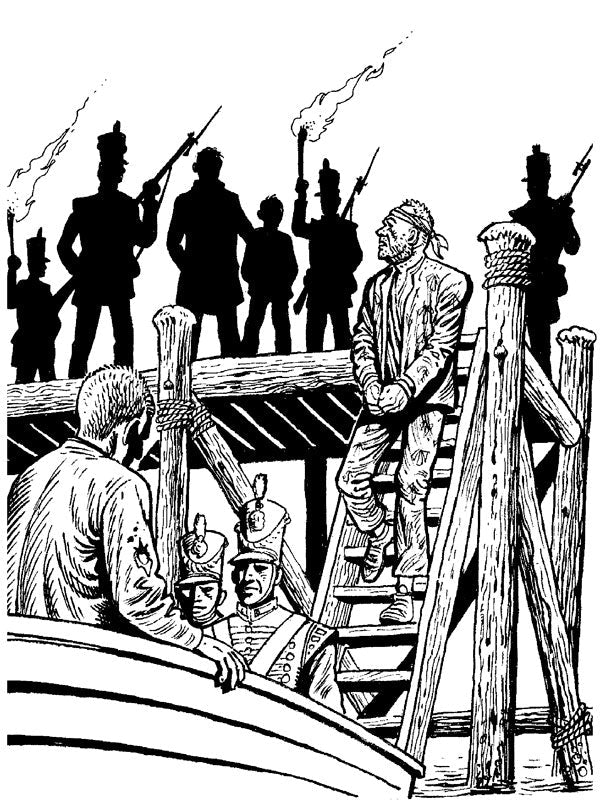

Theft of property under the value of forty shillings (two predecimal pounds) carried a seven year prison sentence; theft over that amount was punishable by hanging! However, not everyone who received the death penalty was hanged and prisoners who were granted a reprieve were selected for transportation instead.

The idea to ship criminals out of Britain started life nearly two hundred years before Dickens was born (and while Shakespeare was still alive). In 1597, an act was passed to “banish dangerous criminals from the Kingdom”; but it took until 1615 for the first convict ships to leave England. Back then, they were sent to America. This continued for over a hundred and fifty years; but with the War of Independence in 1775, the American colonies closed their ports to British prison ships, and a new destination had to be found.

The British government decided upon New South Wales (Australia) and the first convicts left Britain in 1787. The area formally became a British Colony in 1788, and from then until 1868 when transportation ended, 165,000 convicts were sent there.

But before New South Wales became the replacement destination, a solution had to be found to house the growing number of convicts awaiting deportation. As a temporary solution, they decided to warehouse these convicts in old warships moored in the River Thames. These Prison Hulks were soon treated as the answer to the generally overcrowded prisons with conditions on these floating prisons even worse than those on land.

One famous hulk, The Warrior, comprised three decks, each holding 150 to 200 convicts. The decks were divided into caged cells on both sides of the hull, with a walkway down the middle. Each cell housed eight to ten men, with only the old gun ports in the sides of the hull for ventilation.

The hulks were terribly unsanitary. Not only were there problems caused by the overcrowded living conditions, but all water was taken from the polluted Thames; and this gave rise to outbreaks of diseases like cholera and dysentery.

By 1850, the use of hulks was in decline; and in 1857, the last hulk was destroyed.

Although hulks were no longer in use when Dickens started to write Great Expectations (1860), their presence in the book is not an error. The hulks appear at the start of the book, which is set in 1812 – a time when the use of hulks was probably at their peak.